Picture This: A History of Northland Poster Collective

Images are the best way to tell the story of Northland Poster Collective.

Picture this: The Northland Cultural Workers' Conference in Minneapolis, 1979. Eleven young graphic artists meet in a workshop, and excitedly feed off one another's ideas about using art to chronicle and create social change.They meet again, and again, eventually forming a collective to critique one another's art. Lisa Blackshear, Dean Conners, Marilyn Hall, Lee Hoover, Richard Kees, Ricardo Levins Morales, Janice Perry, Frank Sander, Carla Stetson, Mary Sutton, and Lee Wolfson belong to this early incarnation of the collective. George Beyer, an artist who cut his teeth during the CIO organizing drive of the 1930s, delightedly attends their meetings. He encourages them to use silk screening to put their art into circulation.

Picture this: The first Northland catalog, a single 11 X 17

piece of paper run off on a black and white photocopier, containing sixteen posters.The subject matters reflect the

political interests of the artists: Chile: "!La Resistencia Continua!," "Zimbabwe African National Union 1979:The Year of

People's Storm," "Introducing the Neutron Bomb (Paid for With Your Own Tax Dollars)," "May Day: The First and Only

International Labor Day," "Sanrizuka, Japan: Farmers United Against the Airport and For the Land," and Olive Schreiner's

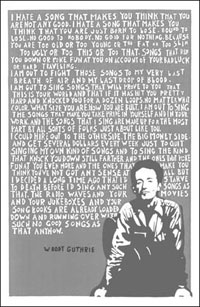

poem "I Saw a Woman Sleeping." One of the posters, a lengthy quote from Woody Guthrie's autobiography Born to Win, is

destined to become a best seller. "I just had to get that one out of my system," Ricardo, the artist, explained later.

"With all those words, I didn't really expect anyone to buy it. I made it for myself, because it summarized what I wanted to do

with my life. As it turned out, we couldn't keep up with the demand." For the first printing, Ricardo patiently cuts each letter out

from a translucent lacquer-based film. He then presses this onto the silk screens to print the posters by hand. Today the Woody

Guthrie poster is off-set printed, having sold over 7,000 copies.

Picture this: The first Northland catalog, a single 11 X 17

piece of paper run off on a black and white photocopier, containing sixteen posters.The subject matters reflect the

political interests of the artists: Chile: "!La Resistencia Continua!," "Zimbabwe African National Union 1979:The Year of

People's Storm," "Introducing the Neutron Bomb (Paid for With Your Own Tax Dollars)," "May Day: The First and Only

International Labor Day," "Sanrizuka, Japan: Farmers United Against the Airport and For the Land," and Olive Schreiner's

poem "I Saw a Woman Sleeping." One of the posters, a lengthy quote from Woody Guthrie's autobiography Born to Win, is

destined to become a best seller. "I just had to get that one out of my system," Ricardo, the artist, explained later.

"With all those words, I didn't really expect anyone to buy it. I made it for myself, because it summarized what I wanted to do

with my life. As it turned out, we couldn't keep up with the demand." For the first printing, Ricardo patiently cuts each letter out

from a translucent lacquer-based film. He then presses this onto the silk screens to print the posters by hand. Today the Woody

Guthrie poster is off-set printed, having sold over 7,000 copies.

Picture this: Collective members at the public library, compiling a mailing list by copying names and addresses of progressive bookstores around the country from the Yellow Pages. Collective members printing posters and filling orders in the basement of a former grocerystore on the corner of Bloomington and Franklin Avenues, which also houses the Northern Sun Anti-Nuclear Alliance and its fund-raising arm, Northern Sun Merchandising. Some collective members losing interest, as filling orders and sending out catalogs becomes a larger part of the weekly routine.

Picture this: Northland's second home, on the third floor of a warehouse on North Washington Avenue in Minneapolis (currently housing Sex World -- a rather different story!). Ricardo, Richard, Barry Beckel-Kleider, Lee Hoover, and Lois Beckel filling orders on their lunch breaks and odd hours. Excited responses from progressive bookstores and from political artists around the country, who encourage the collective to gather and distribute the work of even more artists. Collective members attend a couple of seminars on mail-order marketing, and learn that there is a science to what they are trying to do!

Picture this: The Northland catalog of 1988,

printed on glossy paper and in color for the first time, with Rosie the Riveter rolling up her sleeve above a

union bug on the cover. Inside, twelve packed pages of posters covering union issues; the anti-apartheid

struggle in southern Africa; the Central American solidarity movement in the US; the nuclear weapons freeze

campaign; women in the labor movement; and--for the first time--non-poster items like books, records, and

post cards.The collective has made a particular effort to get art from labor artists, and labels everything that

is union-printed. The color catalog is the beginning of Northland's serious debt, though, since it can only be

financed with the help of family and friends.

Picture this: The Northland catalog of 1988,

printed on glossy paper and in color for the first time, with Rosie the Riveter rolling up her sleeve above a

union bug on the cover. Inside, twelve packed pages of posters covering union issues; the anti-apartheid

struggle in southern Africa; the Central American solidarity movement in the US; the nuclear weapons freeze

campaign; women in the labor movement; and--for the first time--non-poster items like books, records, and

post cards.The collective has made a particular effort to get art from labor artists, and labels everything that

is union-printed. The color catalog is the beginning of Northland's serious debt, though, since it can only be

financed with the help of family and friends.

Picture this: The eleventh Great Labor Arts Exchange in Washington, D.C., in 1989. Ricardo attends, to lead a workshop on "Giving the Boss an Art Attack." Other participants at the conference gobble up the merchandise he brings, encouraging the collective to begin attending labor conventions around the country to sell their products. Ricardo becomes a popular workshop leader, helping labor activists come up with ideas for mixing art into their organizing, and Northland continues to be a regular fixture at the Great Labor Arts Exchange every June.

Picture this: Union-made t-shirts appear in the first catalog of the new decade. Ricardo has quit his day job at Cold Side Silkscreening and set up his own business, RLM Graphics. All the printers join the International Brotherhood of Painters and Allied Trades. RLM Graphics supplies most of Northland's products from then on. Although technically two separate businesses--one a non-profit and the other a sole proprietorship-- Northland and RLM Graphics are run as one collective.

Picture this: Sheets of butcher paper on the walls as the collective engages in visioning and

decision-making. The collective--Ricardo, Barry, Lee, Lois, and Barb McAfee--is solid, and feels certain of

what it wants to do politically. However, a warehouse is no place to welcome visiting trade unionists--especially

when one has to run down three flights of stairs to let them in through the locked door--and they are running out

of space. So the collective rents two side-by-side storefronts on Lake Street in 1990, and moves again.

Picture this: Sheets of butcher paper on the walls as the collective engages in visioning and

decision-making. The collective--Ricardo, Barry, Lee, Lois, and Barb McAfee--is solid, and feels certain of

what it wants to do politically. However, a warehouse is no place to welcome visiting trade unionists--especially

when one has to run down three flights of stairs to let them in through the locked door--and they are running out

of space. So the collective rents two side-by-side storefronts on Lake Street in 1990, and moves again.

Picture this: The 1991 catalog converts to a black and white, newspaper tabloid format. "This move from color to black and white catalogs was in response to financial realities," the collective admits in its "dear friends" letter inside. "The cost of competing for attention with slick, glossy advertisers was making it harder to do what we're here for: providing inspiring, educational material for activists, organizers, teachers, and their friends. We can now print smaller monthly runs . . . and respond much more quickly to public events and to feedback from you, the people on the frontlines of the labor, peace, environmental, and justice movements." The "financial realities" include a deepening spiral of debt to suppliers, the state of Minnesota, and the IRS. The move itself takes longer and costs more than they expect. Fortunately, Northland's customers are just as excited by products pictured in black and white as in color.

Picture this: An increasingly multi-cultural collective and some friendly creditors. As often happens in a move, people burn out, and in Northland's case some people who've already helped out on occasion take on more responsibility. Rahel Hewit-Herzog, Julie Horns, Mali Kouanchao, and Simone Senogles provide enthusiasm and fresh energy. In order to keep going, Ricardo presents a well-thought-out business plan to a group of socially-conscious investors, and borrows more money. The IRS and the state of Minnesota are temporarily appeased.

Picture this: The 1993 catalog introduces products specifically geared to union organizing drives and contract negotiations. Slogans such as "The Labor Movement: The Folks Who Brought You the Weekend," and "Beware: Keep Hands Off Benefits," and "Safety:We Come to Work, Not to Die" appear on bumper stickers, buttons, and decals. Meanwhile, a small and growing number of posters lampoon the standard shop floor posters put up by management. Ricardo demonstrates his ability as a cartoonist, with a series of smiley-faced bosses trying to hood-wink workers with strategies like the Team Concept.These 11 X 17 posters, run off on photocopiers, are priced to be ripped down by infuriated management, and replaced the very next day.

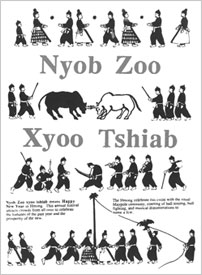

Picture this: A series of posters by Asian-

American artists; a series of posters by and about African-Americans; a series of portraits of labor

leaders. Northland products begin to appear in classrooms around the country, as teachers take advantage

of a 10% educational discount.

Picture this: A series of posters by Asian-

American artists; a series of posters by and about African-Americans; a series of portraits of labor

leaders. Northland products begin to appear in classrooms around the country, as teachers take advantage

of a 10% educational discount.

Picture this: Stacks of unopened envelopes from the IRS in the collective bookkeeper's desk

drawers. In trying to avoid "founder's syndrome" and have an egalitarian collective, Ricardo hasn't checked very

carefully on what the bookkeeper's been doing. Turns out that the bookkeeper shares Ricardo's disregard for

paying bills! Repeated trips to the IRS office in Bloomington, trying to understand which forms need to be

completed, and what the appeals process might do for the collective. Earnest negotiations with suppliers,

printers, and banks. A winter spent in the building without heat because the landlord has not been paying the

gas bill. No water because the pipes burst in the cold. "The collective" sometimes dwindles to Ricardo and Jeff

Peterson, the printer, because no one else can work without pay. Nervous meetings with extremely patient and

kind creditors, who offer their best advice and help. A sympathetic column by Doug Grow in the Minneapolis

Star and Tribune detailing Northland's troubles results in a completely unexpected and highly generous gift of

$18,000 to keep the IRS at bay. These are some of the images of the mid-1990s. Not everything happens at

once, but it all adds up to several near-death experiences, and some unpleasant memories. When a friend asks

Ricardo why he sticks it out, Ricardo answers honestly, "I think it's because I look forward to telling the story

and saying, 'It really wasn't worth it!'"

Picture this: Postal workers in Danbury, CT, greet

their regional manager wearing red t-shirts proclaiming, "Bosses Beware: When We're Screwed,We Multiply."

Up until then, the workers have been protesting in vain as their local management violated important provisions

of their contract. The attack of the militant bunnies, however, breaks the impasse --suddenly, management is

paying attention! The bunny shirts come from Northland Poster Collective, of course.

Picture this: Postal workers in Danbury, CT, greet

their regional manager wearing red t-shirts proclaiming, "Bosses Beware: When We're Screwed,We Multiply."

Up until then, the workers have been protesting in vain as their local management violated important provisions

of their contract. The attack of the militant bunnies, however, breaks the impasse --suddenly, management is

paying attention! The bunny shirts come from Northland Poster Collective, of course.

Picture this:

Articles about the feisty artists in the heartland appear in the national magazines of the carpenters, chemical

workers, auto workers, and in the National Catholic Reporter. Northland images and slogans are borrowed (with

and without attribution!) for union newsletters and organizing drives across the country. Northland's posters are

a familiar sight on the walls of many union halls, and even hang in the AFL-CIO headquarters in Washington, D.C.

Picture this: The launch of Northland's web site, one of the first e-commerce sites on the internet, in 1996.

Alejandro Levins, Ricardo's brother, designs and programs it. Drawing inspiration from digital technology, Ricardo puts

together a new business plan which anticipates Northland's best-selling images on many surfaces: mugs, mousepads,

note cards, temporary tattoos, and screen savers. A new line of baby and youth garments and bibs bring coos

and cries of "How cute!" at conferences.

Picture this: The launch of Northland's web site, one of the first e-commerce sites on the internet, in 1996.

Alejandro Levins, Ricardo's brother, designs and programs it. Drawing inspiration from digital technology, Ricardo puts

together a new business plan which anticipates Northland's best-selling images on many surfaces: mugs, mousepads,

note cards, temporary tattoos, and screen savers. A new line of baby and youth garments and bibs bring coos

and cries of "How cute!" at conferences.

Picture this: An incredibly dedicated group of young environmental activists camp out in front of bulldozers for 18 months to prevent the widening of Highway 55 from 46th Street to the Mall of America.Their experience in self-governing, consensusbased community life creates a new wave of anarchist collectives in the Twin Cities. Northland benefits, as Whitney Fink leads a steady stream of her friends tothe storefront on Lake Street, where they take jobs. Angie Anderson, Austin Beatty, Keith Jackson, Sarah Jordan (Lawton), Emily Lindell, and Ben Tsai are among them. Betsy Raasch-Gilman joins the collective in 1999 as a bookkeeper. Her business experience, mostly gained in food co-ops, brings much-needed sanity. Both Ricardo and his creditors breathe a huge sigh of relief as Betsy doggedly whacks away at a jungle of financial brambles, and puts into place basic management systems.

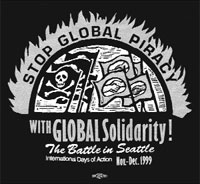

Picture this: Excitement is building

about a major demonstration in Seattle during the meeting of the World Trade Organization. An organizer friend

there tells Ricardo, "You know, there's no official t-shirt for this event yet." Holding their breaths, Ricardo and

Betsy borrow yet more money to finance an enormous run of t-shirts, pack them into Sarah's battered truck,

and Sarah drives them over the Rockies. In the most intense retail experience ever, Ricardo and Betsy sell

Northland productsto 20,000 enthusiastic trade unionists rallying at Memorial Stadium. Reports of tear gas and

rubber bullets reach them as they sell. Later, as they pack up, they realize that they are trapped by the state of

emergency declared by Seattle's mayor.

Picture this: Excitement is building

about a major demonstration in Seattle during the meeting of the World Trade Organization. An organizer friend

there tells Ricardo, "You know, there's no official t-shirt for this event yet." Holding their breaths, Ricardo and

Betsy borrow yet more money to finance an enormous run of t-shirts, pack them into Sarah's battered truck,

and Sarah drives them over the Rockies. In the most intense retail experience ever, Ricardo and Betsy sell

Northland productsto 20,000 enthusiastic trade unionists rallying at Memorial Stadium. Reports of tear gas and

rubber bullets reach them as they sell. Later, as they pack up, they realize that they are trapped by the state of

emergency declared by Seattle's mayor.

Picture this: A high-end laser copier appears at Northland. Central heat and air conditioning follow, because otherwise it won't work (machines being more finicky than activists)! The copier revolutionizes production, making cheap 11 X 17," off-set quality, color posters and note cards possible. Clerical workers at the University of Minnesota give the machine its first major test, with an order of 15,000 posters for a multi-year campaign to improve their wages and benefits.

Picture this: Artist Janna Schneider hunched over the mailing room table, drawing images of people's movements during the 20th century. Century of Struggle, an artistic collaboration between Janna and Ricardo, appears in the 2000-01 catalog. Over 600 campaigns, leaders, newspapers, and organizations appear.The images are grouped into the shape of a tree. Movements of the 1900s are the roots, the �60s are the trunk, and the �70s, �80s, and �90s form the entire canopy of leaves. (Century of Struggle poster featured on the following page of this program.)

Picture this: Airplanes slamming into the World Trade Center towers in New York. Northland workers

grimly trying to guess the political impact. An anti-war demonstration scheduled in Minneapolis for the following

Monday.The collective leaps into action, imagining an 11 X 17" sign that people can display in their windows or

carry at rallies. Emily and Ricardo poll their friends over the weekend for slogans that might express activists'

concerns. At lunch on Monday, the collective decides on words and images. Alex Bajuniemi goes to his computer

and designs the window sign. Others review it, change a word, and it goes into production. At the rally at 4:30,

collective members pass out the No War window sign, and it is welcomed heartily.The next day it is on the web

site as a free, down-loadable poster. A grant from the Twin Cities Friends Meeting (Quakers) finances an off-set

print run, and ultimately over 7,000 copies go into circulation. Other shops reprint it.The recession following

the 9/11 attacks once again nearly kills Northland, yet not even Betsy regrets giving away all these posters.

Picture this: Airplanes slamming into the World Trade Center towers in New York. Northland workers

grimly trying to guess the political impact. An anti-war demonstration scheduled in Minneapolis for the following

Monday.The collective leaps into action, imagining an 11 X 17" sign that people can display in their windows or

carry at rallies. Emily and Ricardo poll their friends over the weekend for slogans that might express activists'

concerns. At lunch on Monday, the collective decides on words and images. Alex Bajuniemi goes to his computer

and designs the window sign. Others review it, change a word, and it goes into production. At the rally at 4:30,

collective members pass out the No War window sign, and it is welcomed heartily.The next day it is on the web

site as a free, down-loadable poster. A grant from the Twin Cities Friends Meeting (Quakers) finances an off-set

print run, and ultimately over 7,000 copies go into circulation. Other shops reprint it.The recession following

the 9/11 attacks once again nearly kills Northland, yet not even Betsy regrets giving away all these posters.

Picture this: A poster expressing outrage over the racist response to Hurricane Katrina. Buttons and bumper stickers emphasizing the value of Social Security. A poster celebrating US labor solidarity with China. T-shirts for anti-war activists. A note card comparing the force of people�s movements with the force of a volcano. A poster commemorating Haitian hero Toussaint L'Overture.The collective--Austin Beatty, Kim Christoffel, Lila Karash, Ricardo Levins Morales, Eduardo Penasco, Betsy Raasch-Gilman, Qamar Saadiq Saoud, and Janna Schneider--work them into the 2005-06 catalog, load them onto the web site, and send them out to a wide, supportive network of activists.

The phones are ringing. Every day come calls about front line struggles: military families protesting the war

in Iraq; activists fund-raising for undocumented farm workers hit by the hurricane; striking mechanics at

Northwest Airlines; California teachers facing budget cuts.The corporate media declares that mass movements

are a thing of the past. At Northland, we're too busy to notice.

--Betsy Raasch-Gilman